Education, Equality, and Demographic Shifts: The Changing Landscape for Women

Education, Equality, and Demographic Shifts: The Changing Landscape for Women

Published on :- March 13th, 2025

On March 8, 2025, we celebrated International Women’s Day under the UN theme: "For ALL Women and Girls: Rights. Equality. Empowerment." This theme highlighted the urgency of accelerating progress toward gender equality, and called for concrete action to ensure equal rights, power, and opportunities for all. The focus is on empowering young women and adolescent girls, positioning them as catalysts for lasting change.

How can we drive progress?

Support strategies and resources that help women advance

Challenge discrimination and bias

Celebrate women's achievements

Share knowledge and encouragement

By taking these steps, we can foster a more inclusive and equitable society.

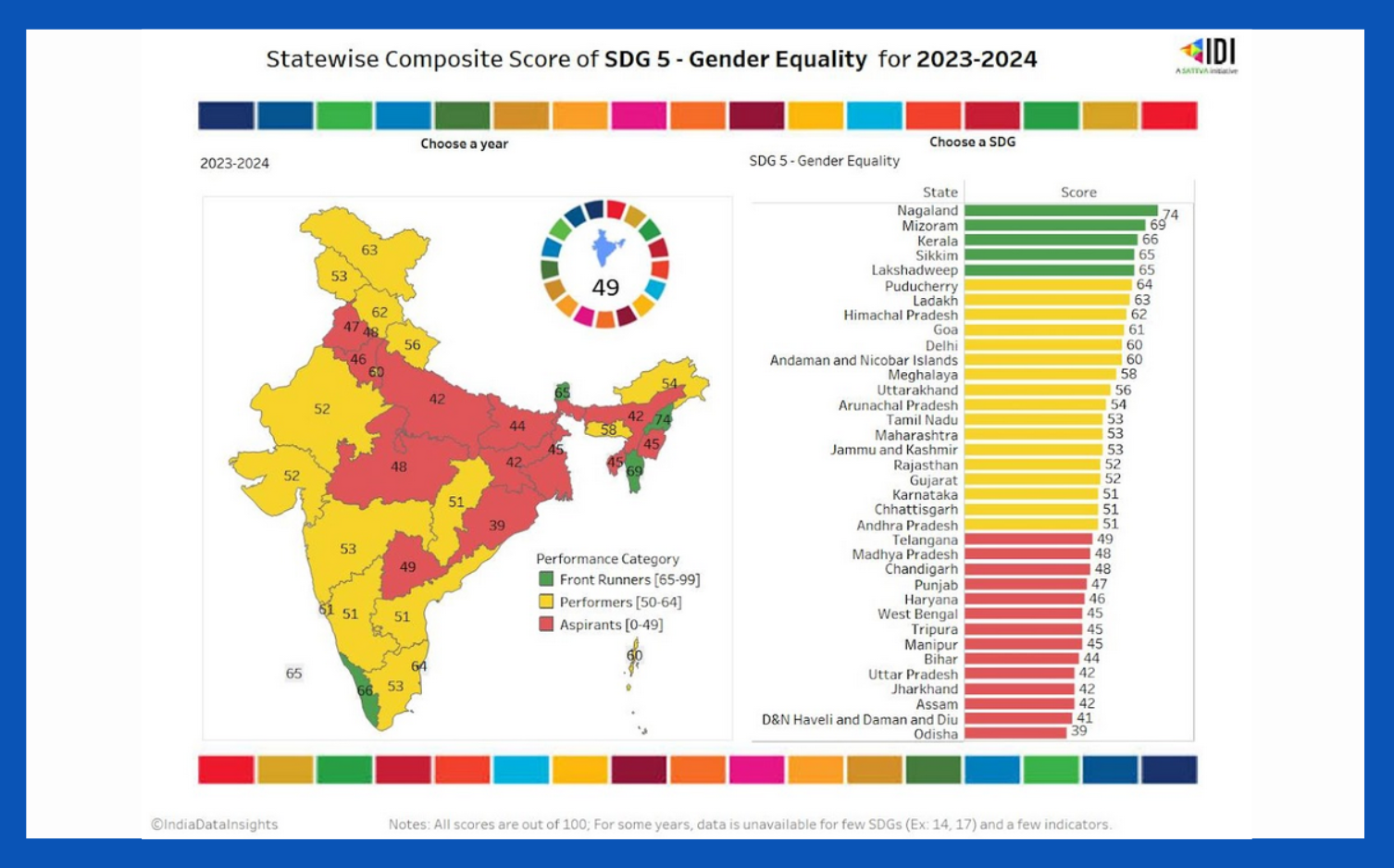

This month's Data Dialogue explores the shifting landscape for women, as efforts toward their empowerment evolve. The primary objective of SDG 5 is to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. According to NITI Aayog’s Sustainable Development Report 2024, India’s overall SDG 5 score stands at 49 out of 100, with 14 states scoring below the national average. This indicates a considerable need to advance gender equality in these regions.

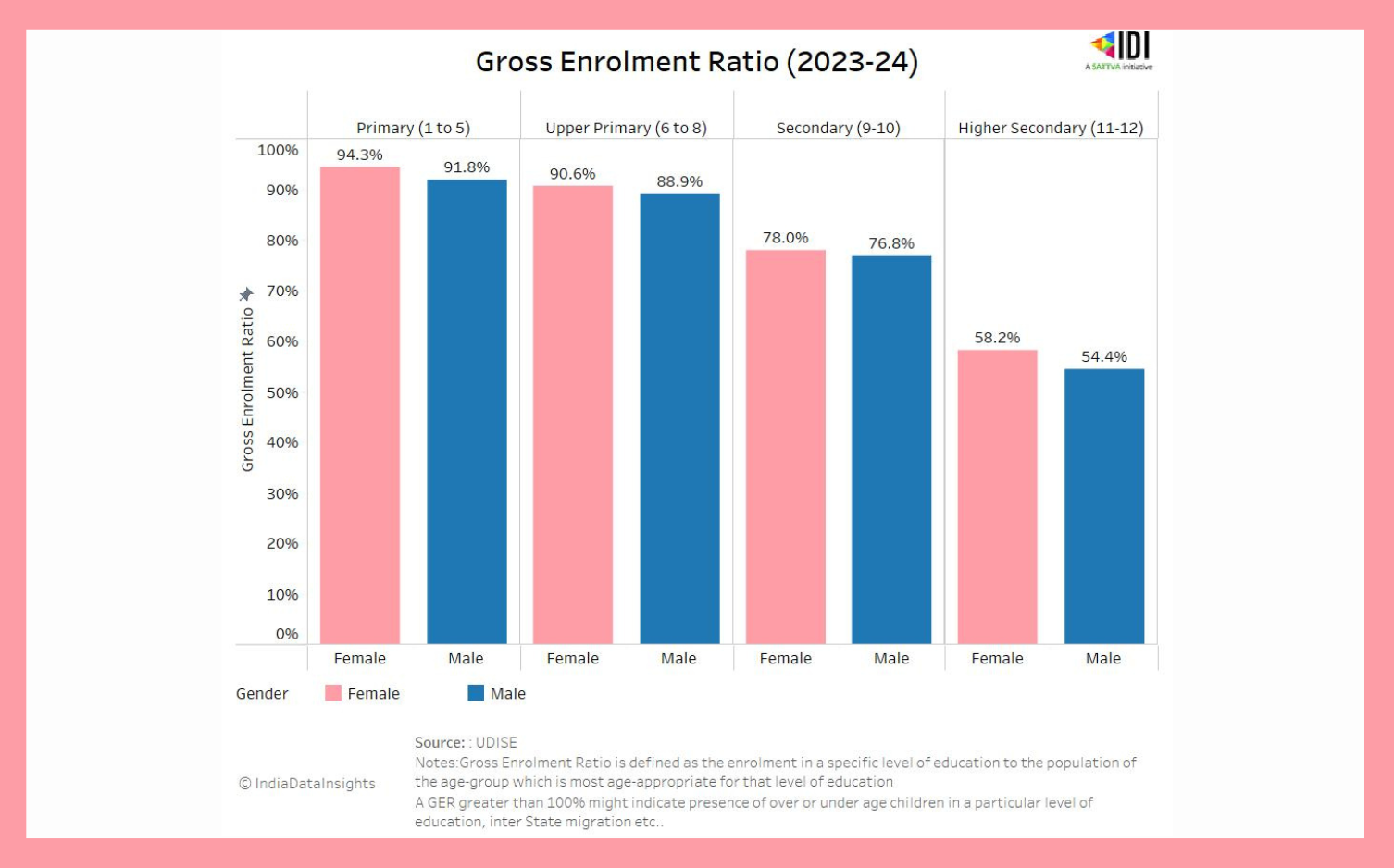

Education plays a crucial role in bridging gender inequality. As of 2023-24, India has 23.4 crore total students enrolled from primary to higher secondary levels, with girl students making up 48% of total enrolments. Encouragingly, girls consistently have a higher Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) than boys across all levels of education, reflecting progress in gender equity.

However, dropout rates among these students rise significantly at the secondary and higher secondary levels, which limits access to higher education and career opportunities. Addressing this gap is essential for women’s empowerment and overall national development.

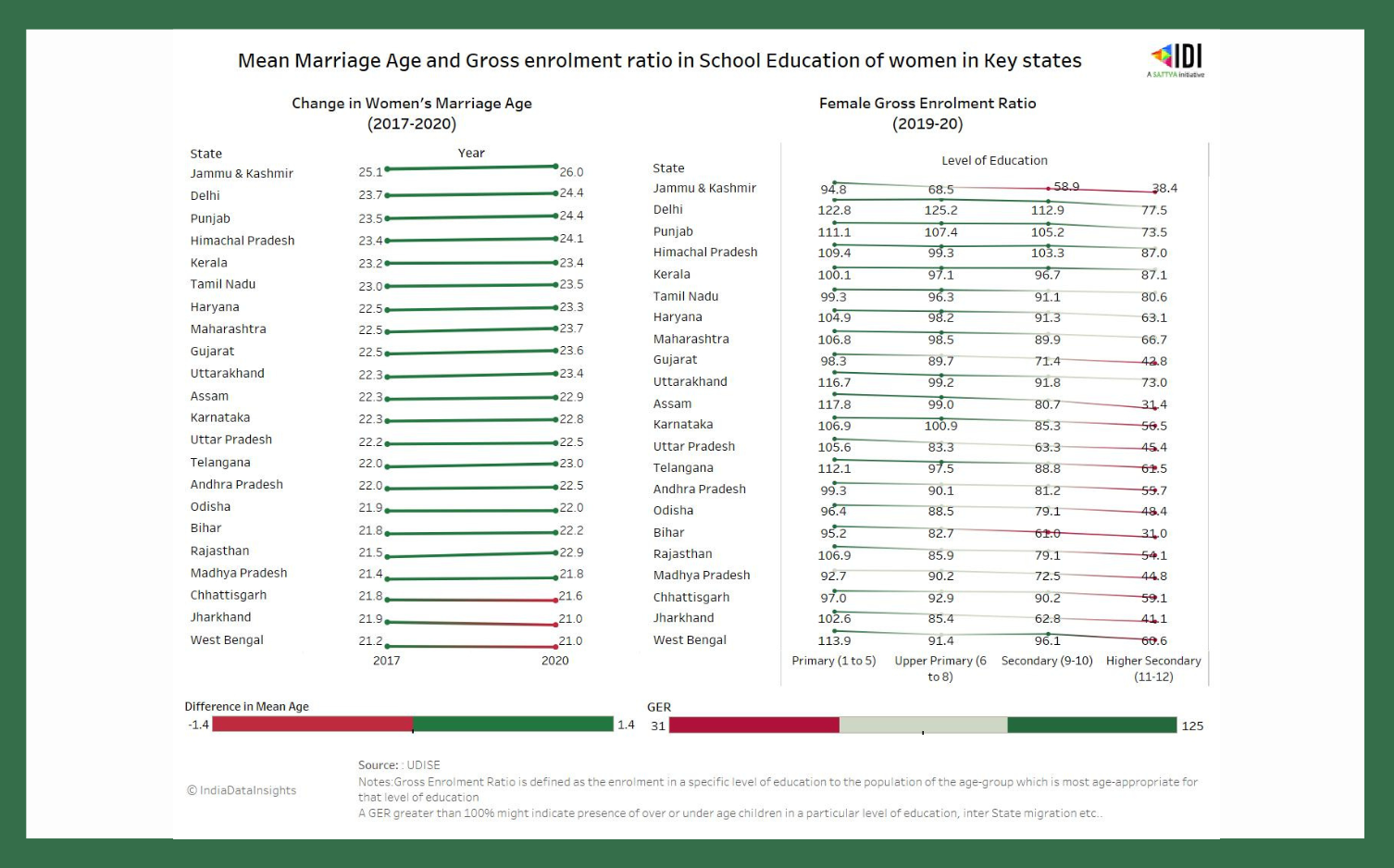

While women's participation in education has increased over time and now surpasses male participation at all levels, this trend coincides with a rise in the average marriage age for women in India, which grew from 22.1 years in 2017 to 22.7 years in 2020.

Most key states have experienced a rise in women's marriage age, reflecting a shift towards delayed marriages. However, states like Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh continue to have lower average marriage ages, around 21 years, along with female enrolment in higher education at a low — 41.1% and 59.1% respectively as of 2019-20.

While states such as Gujarat, Assam, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh have seen an increase in the average marriage age between 22 and 23 years, their female gross enrolment ratio as of 2019-20 in higher education remains below 45%.

Notably, states with a higher female marriage age—such as Kerala, Himachal Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu—tend to have stronger enrolment rates in higher education, above 80% as of 2019-20. Meanwhile, Jammu & Kashmir, despite an increase in marriage age, continues to show consistently low female enrolment from upper primary levels and beyond.

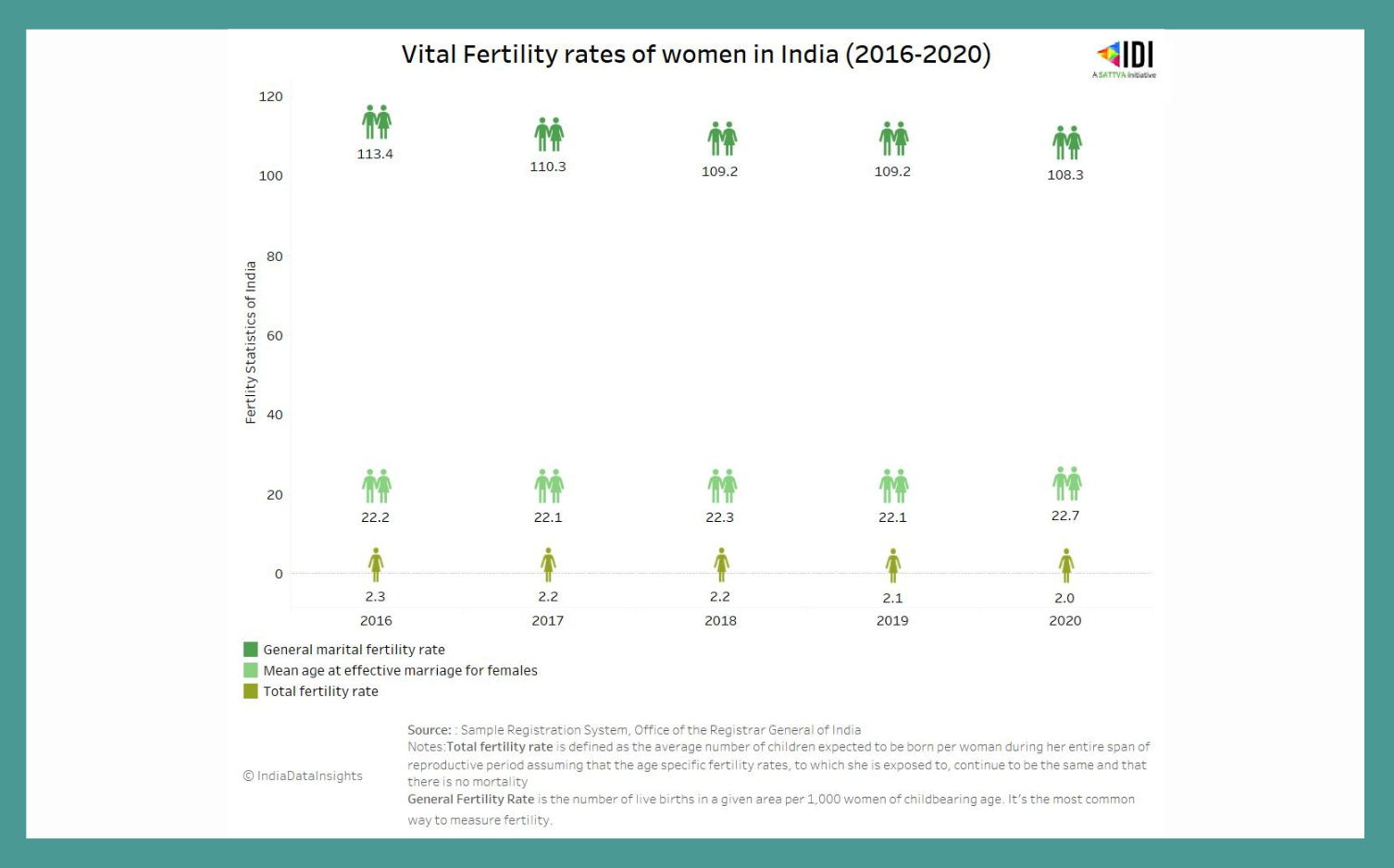

With changing trends in women’s mean age of marriage, India has also observed a decline in birth rates among married women aged 15-49, from 113.4 live births per 1,000 women in 2016 to 108.3 in 2020. The country has moved below the replacement fertility level* of 2.1. Over the past five years, the average number of children a woman is expected to have has decreased from 2.3 children per woman in 2016, to 2.0 in 2020.

*Note: Replacement level of fertility is the average number of children a woman needs to have to maintain a population.

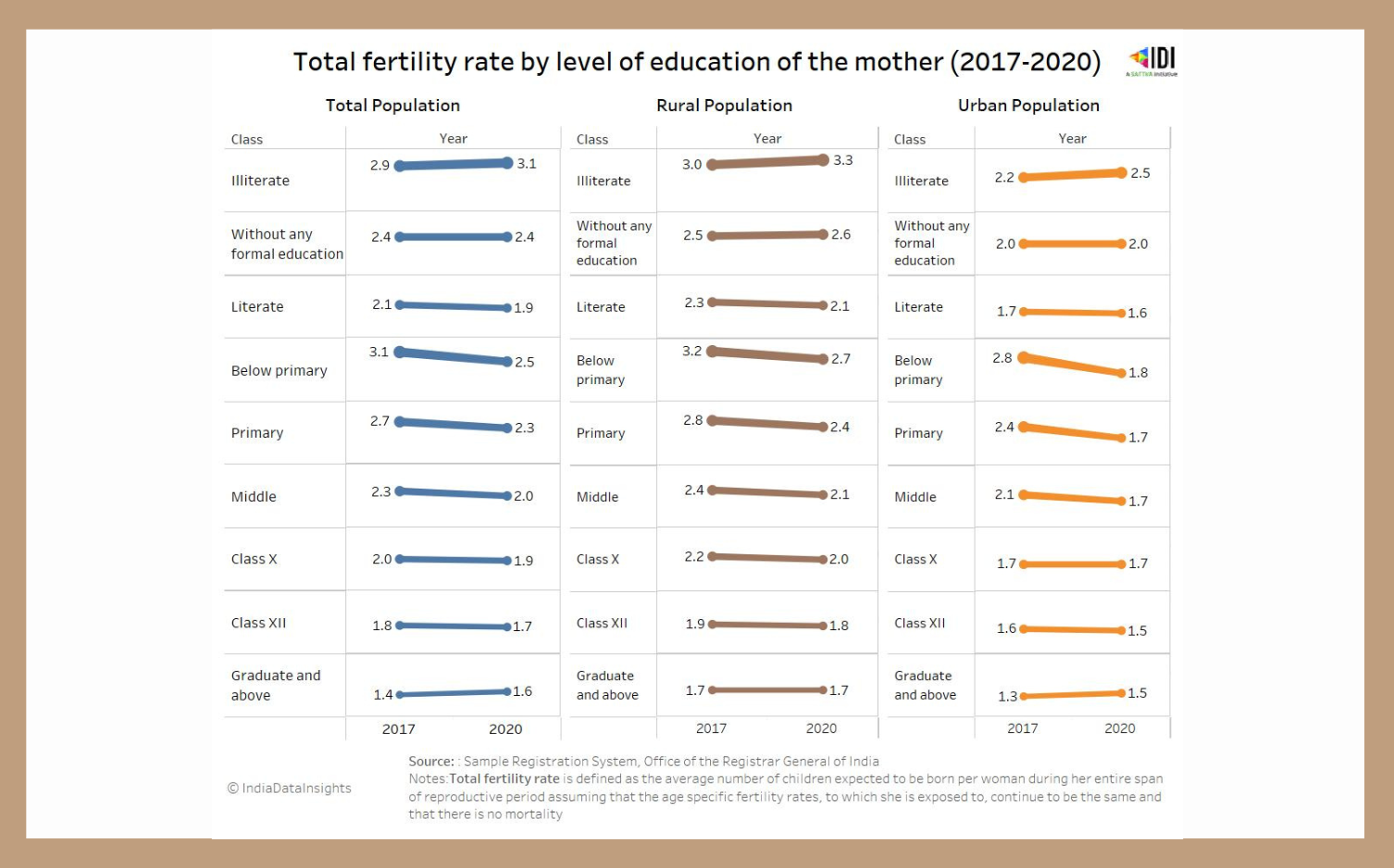

Mothers’ educational levels are a key factor influencing these fertility rates. There is a clear link between total fertility rates (TFR) and a mother’s education level—women with advanced educational backgrounds tend to have fewer children.

Overall, women with education up to Class X or higher tend to have two or fewer children. Although the TFR for graduate mothers rose from 1.4 to 1.6 children per woman between 2017 and 2020, it remains below the replacement fertility rate of 2.1. Across nearly all education levels, TFRs have declined during this period.

While education remains a key determinant of fertility patterns, even less educated women in urban areas have experienced declining fertility rates. The most significant drop was observed among urban women with below primary education, where fertility rates fell from 2.8 to 1.8.

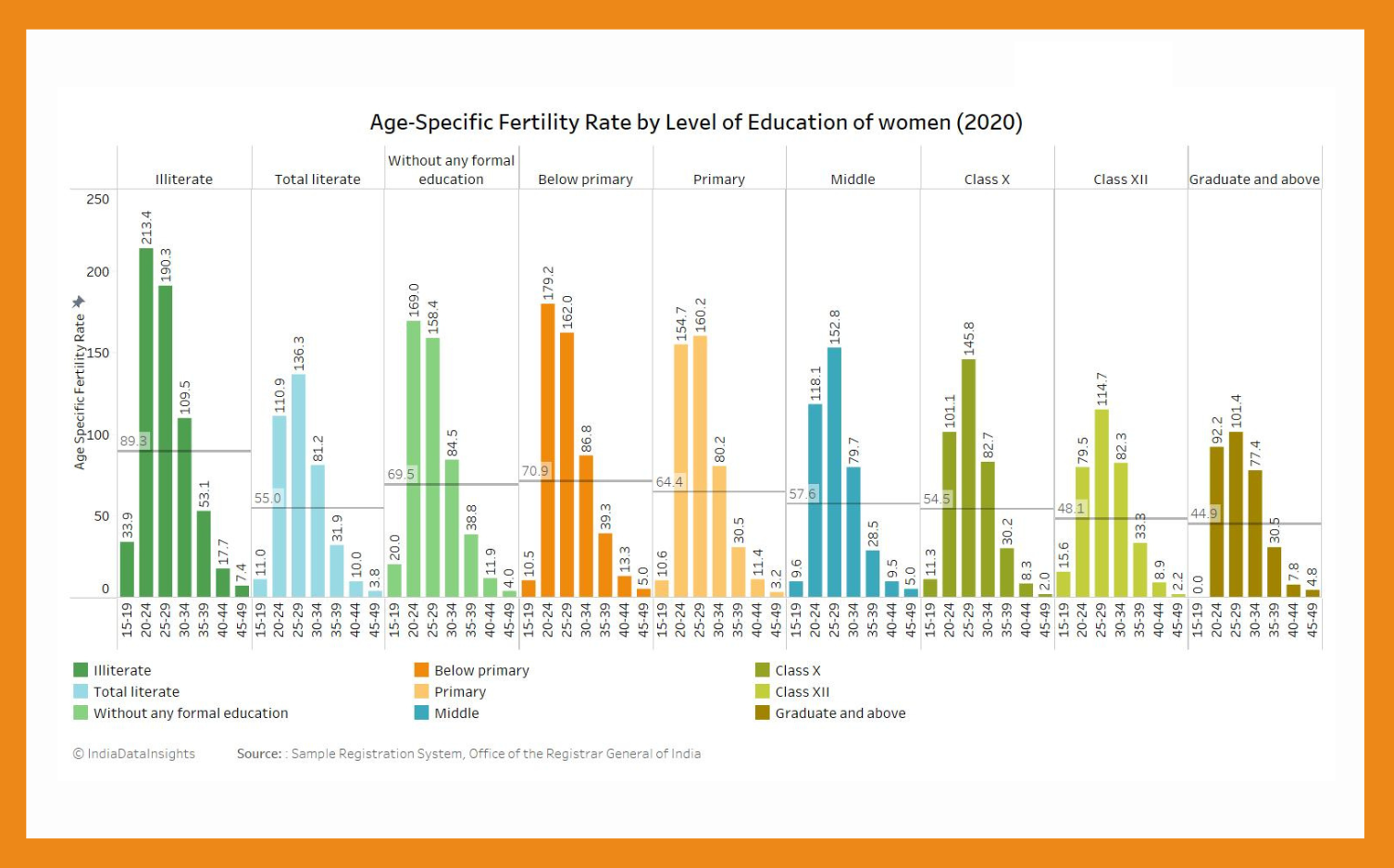

The Age-Specific Fertility Rate (ASFR), which measures the number of births per 1,000 women within a specific age group, highlights significant disparities based on education levels. Women with lower education levels (illiterate, below primary, and primary) continue to have significantly higher fertility rates, especially between ages 20 to 29. Illiterate women aged 20-24 give birth to 213 children per 1,000 women in this group, more than twice the rate among graduates (92 births per 1,000 women).

As of 2020, the average number of births per thousand “illiterate” women was more than 50% higher than that of births per thousand “literate” women, underscoring the significant impact of education on fertility rates.

A particularly sensitive fertility indicator is the adolescent fertility rate (15-19 years), which reveals stark differences based on education levels. Among illiterate adolescent women, the rate stands at a high 33.9 live births per 1,000, compared to just 11 per 1,000 among their literate counterparts. This rate drops to zero for graduates and above, and remains significantly lower (20.0) even for those who are literate but lack formal education.

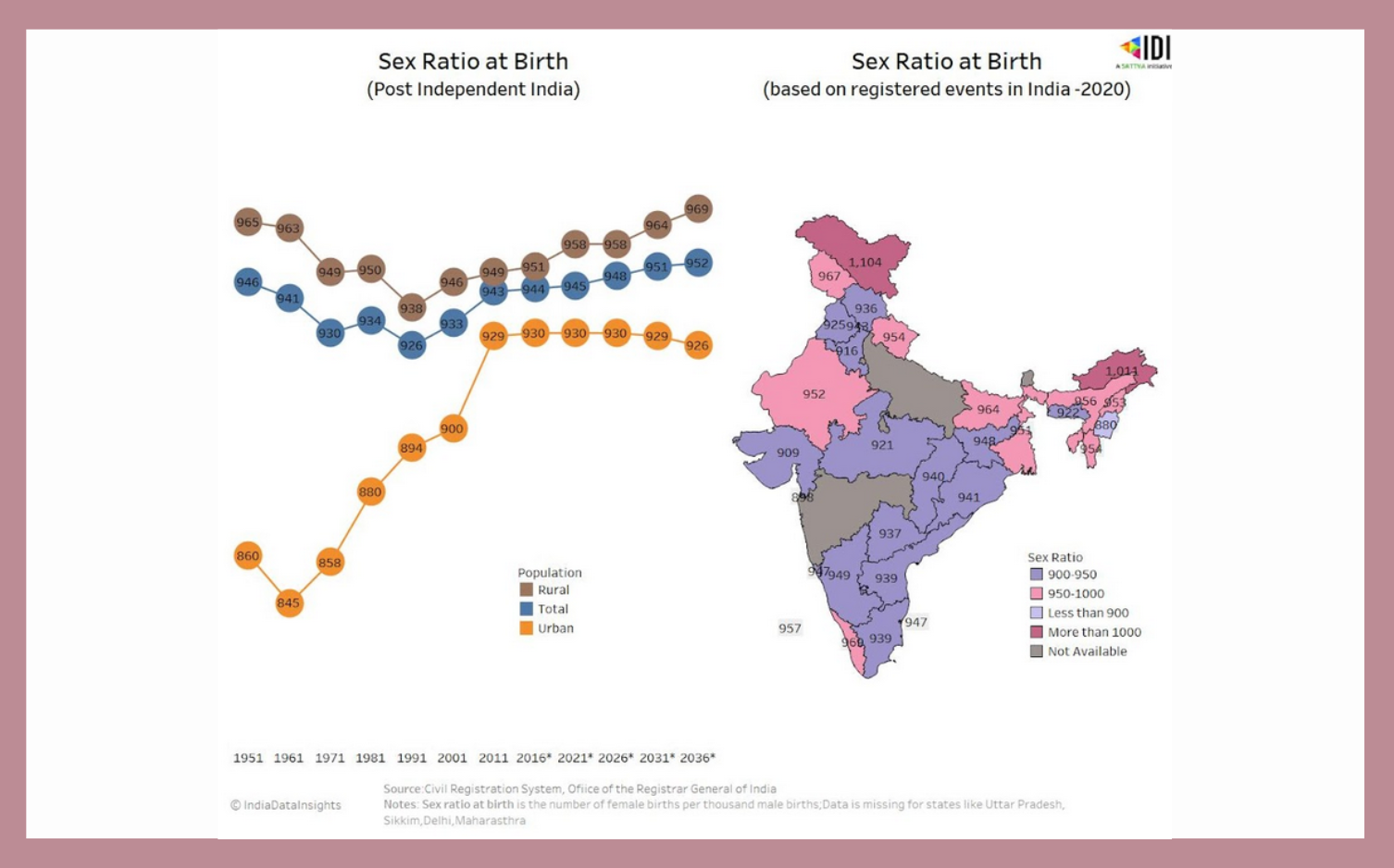

While declining fertility rates and increasing female participation in education are influencing India’s overall population growth, gender imbalance in the population distribution remains a concern.

Historically, the sex ratio at birth has fluctuated significantly. The urban sex ratio improved from 860 females per 1,000 males in 1951 to 929 in 2011, while the rural sex ratio declined from 965 to 949 over the same period.

As per the MoHFW, the national average is projected to remain around 950 females per 1,000 males by 2036, indicating a persistent gender imbalance; and as of 2020, 60% of Indian states and UTs (19 out of 32) have sex ratios below 950 (based on registered events), with Manipur having the lowest (880 females per 1,000 males). Only Ladakh (1,104) and Arunachal Pradesh (1,011) recorded more female births than male births, an uncommon trend in India.

Empowering women through education, policy reforms, and social initiatives is key to achieving true gender equality. While progress has been made in education, delayed marriage, and declining fertility rates, challenges such as high dropout rates, regional disparities, and gender imbalances persist. By continuing to invest in women's empowerment, India can pave the way for a more inclusive and equitable future.

Explore more assets on Gender Equality, and visit India Data Insights for further insights on SDG 5.